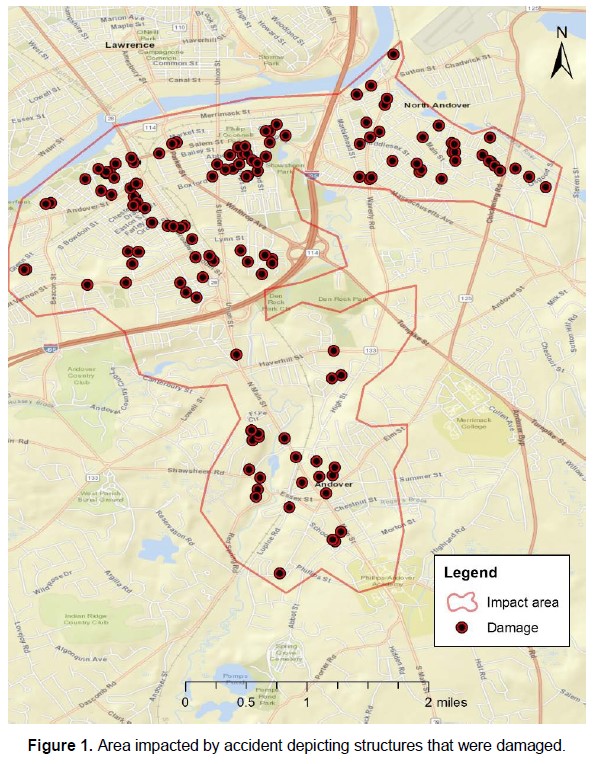

The NTSB released its preliminary report on the recent Columbia Gas pipeline explosion in Northeastern Massachusetts that killed one person, sent 21 others to the hospital, and destroyed or damaged 131 structures. Workers were replacing a cast iron, low-pressure distribution system that was installed in the early 1900s. As workers made the transition from the old distribution line to the new plastic distribution line, it was not taken into account that the sensing lines that fed into the pressure regulators for the low-pressure distribution system were still attached to the old line. As the pressure dropped in the now disconnected old line, operators increased the pressure to the system, seemingly not realizing that they were driving the system into a state of overpressure.

This fact did not go unnoticed by a Columbia Gas remote monitoring center in Columbus, Ohio, which reported high-pressure alarms to the operating center in Massachusetts. The remote monitoring center had no control capability and was thus unable to open or close the valves to stop the flow, so soon after it received the second high-pressure alarm it called another group in charge of meters and regulators in Lawrence, Massachusetts, to relay the message that pressure was building up in the system. The first call to 911 was made a few minutes later, at 4:11 PM. It was almost 20 minutes after this call and the ensuing explosions when Columbia Gas was finally able to shut off the regulator in question, and several hours before the valves were shut off.

This is just a preliminary report and the NTSB investigation is ongoing, but the facts that we already have highlight the importance of work processes and procedures to overall health and safety in all process applications. As the report cites, the work plan put together by the crew replacing the distribution line was approved by Columbia Gas, and yet it contained no provisions for dealing with sensors and their role in the transition to the new distribution line. The sensors were completely overlooked. It’s unclear why this was the case, but the problem of improper procedures is endemic across the process industries and exacerbated by the fact that experienced workers are leaving the process and critical infrastructure industries in droves and there are few new workers in line to replace them. Much of the knowledge around specific procedures in plants has traditionally been passed down from one experienced worker to another. Without a way to digitally capture that knowledge and automate certain procedures or, at the very least, provide guided procedures with best practices built in, these types of incidents will continue to happen.

In a process plant like a refinery or petrochemical facility, this type of incident would have been much less likely because a process safety system would have shut the system down and brought it to a safe state. It’s also likely that gas detectors distributed throughout the facility would have detected the presence of natural gas and workers warned to evacuate the facility. The lag time between when the Columbus remote operations center noticed the overpressure conditions and communicated this to the group in Lawrence was also significant. It also took way too much time for local workers to finally shut off the regulator and gas flow valves.

This highlights the desperate need for critical infrastructure industries to share information more quickly and give operators the ability to take quick action when it is required. The technology exists today where these kinds of alerts could be sent to the people that really need it instantaneously, even through their smartphones or mobile devices. In the offshore industry, for example, centralized remote monitoring centers also have tight integration with the control systems and operators on offshore platforms. If a problem is detected by the remote monitoring system, the people on site know about it right away and know how to take action.

As a Massachusetts native, I had a lot of discussions with friends, relatives, and colleagues back home about the possible cause for this incident right after it happened. Not surprisingly, with all the recent reports of cyber-attacks on critical infrastructure (such as the Industroyer malware attacks that have targeted the power and critical infrastructure industries worldwide and the TRITON/TRISIS malware that specifically targets process safety systems), there was some conjecture that this disaster could have been initiated by a cyber-attack. In this case, however, it appears that we were not a victim of attack but our own worst enemy. By not following good procedures, not taking sensors into account, and not providing a reliable way for the right people to take action at the right time, the conditions were ripe for a totally avoidable incident with tragic consequences. Cybersecurity is important, but it’s useless without good fundamental work processes and intelligent application of technology.